Sleeves are certainly not new technology and experts say that, for the most part, engine builders and machine shops understand the use and functionality well. But is a liner and a sleeve the same thing? Is a hole just a hole? Publisher/Editor Doug Kaufman takes a deeper dive.

By

Doug Kaufman

Sep 21, 2015

Cylinder sleeves and liners

Cylinder sleeves and liners can serve many different functions and may be required for a simple engine repair or performance upgrades. In Larry Carley’s article on sourcing engine blocks, he touches on the challenges of finding quality cores – many of the most desirable blocks have seen been better days, and the cylinder bores may be damaged from misuse or from simply being old.

Sleeves are certainly not new technology and experts say that – for the most part, engine builders and machine shops understand their use and functionality well. But is a liner and a sleeve the same thing? Is a hole just a hole?

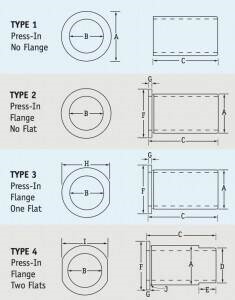

types of cylinder sleeves

Material differences aside, there are two basic types of cylinder sleeves: the dry-type and the wet-type. Simply put, a dry-type sleeve does not contact the coolant, while the wet-type sleeve IS in direct contact with the coolant.

wet sleeve

A wet sleeve, when installed, completes the cooling system. Without the liners in place there is no cooling jacket.

The top is sealed by an interference fit somewhere in the counterbore area and this seal area can include sealing shims or seals. The bottom is normally sealed with O-rings in grooves, which can be either on the sleeve or in the block.

dry-type sleeve

The dry-type sleeve is pressed into a full cylinder that completely covers the water jacket. Because the sleeve has the block to support it, it can be very thin.

Dry liners are not open to the cooling passage of the engine so no sealing ring is required. The dry type sleeves can be used as a new wear surface or as a repair medium for small cracks and holes in the engine block. Dry sleeves require a press fit and machining on the inside after installation.

Brian Zimmerman from Interstate-McBee reminds his customers (typically heavy duty diesel engine shops) about a two-pronged approach to success: cleanliness and measurements.“Cleanliness: Some customers submit claims for cracked liner flanges only to find debris lodged under the liner flange. Or the seals leak at start up only to find the receiver bore was not cleaned prior to assembly,” says Zimmerman. “And your measurements must be performed with quality equipment and recorded! Recording the measurements gives a record of proof of a quality repair (if the necessary work is completed) to your customer and manufacturer if a claim arises. As a technician this record also shows that you know what you are doing and took the time to do the job right.”

Doing the job right takes the proper equipment and training, of course, say our experts. CNC machinery with gauging for on-center bores with the proper tooling, feeds, speeds and cooling will quickly attain the proper finish. But, any experienced machine shop will be able to install efficiently and make money. And, those shops may carry less overhead affording that cushion to keep more in the pocket.

Once cleaned of their metal protectant coating, production wet liners come complete with cross hatch ready to install. Sleeves must be fitted and bored to size. Zimmerman urges caution with fitting the two-cycle dry liners. “Precision and care must be taken when fitting these liners to avoid heat dissipation issues. With new technology constantly knocking at the door these older engines with fitted liners are being service by new technicians who have only been taught wet liner service procedures,” he says. “Same is true for 4 stroke technicians troubleshooting 2 stroke engines – while they are similar they are very different.”

Despite changing engine technology including electric motors, experts agree that sleeving will remain a viable business for the foreseeable future. There are just too many aging blocks around the world.

Flanged-top sleeves are commonly used in aluminum block because their design ensures that the deck surface remains stable. And it is this combination of form and function that allow all of the different styles to work within each recommended application.

Although much of the confusion about use and installation comes from the “guys on the street who are looking to save a few bucks,” according to Dan McDonell from Melling Sleeves, even the experts may have a question of two.

“Many skeptics worry that the sleeves will move or drop after they’re installed,” says Dave Metchkoff from LA Sleeve. “Although that possibility certainly exists, if properly installed they will stay perfectly in place.”

And proper installation is key. Dave Clinton, from Darton Sleeve, suggests that even the guys who should know better sometimes try to take shortcuts. “Some engine guys still want to force the sleeves into a hole,” he says. “The proper method is differential temperature and the hole should have the equal of surface roughness of the sleeve OD. Also using a full-length close-tolerance mandrel and a hydraulic press on all blocks is the best way to get alignment and straight insertion.”

Keep it clean, friend! Some customers submit claims for cracked liner flanges only to find debris lodged under the liner flange. Photo courtesy of Interstate-McBee.

Getting a liner shouldn’t be that difficult these days, according to Darton’s Clinton – what can be challenging is getting the RIGHT part. “Liners are available from hundreds of sources around the world and the US. Typically all production has gone to CNC machining and OD surface grinding. With respect to dimensional tolerances high quality sleeves are available from many world sources, however what separates the product is chemistry and durability, especially in the performance market.”

Melling’s McDonell says the biggest change he’s faced concerns the range of selection. “The biggest thing that has changed now is there are so many choices. I used to have 39 different part numbers for a four-inch bore. Now there are a lot of oddball sizes. 3.870˝, 3.660˝ – to fill the market you have to have a lot of oddball sizes.

This, he says, is driven from the proliferation of new engine designs. “The OEM has gone to lighter blocks and different bore/stroke combinations – what used to be a pretty common four inches is now all over the place,” McDonell says.

“And we do a lot of custom sleeves for guys – the boring bar will slip in the machine shop and they’re stuck,” McDonell says. “They’ll be boring the block and something will happen and all of a sudden they’re 30 thou oversized… they call in a panic, but we can do them in five days.”

Zimmerman agrees that the aftermarket has an edge, thanks to technology. “New technology has allowed manufacturers to offer higher quality liners and parts at a reduced price. Aftermarket manufacturers are producing lower cost parts with quality similar to the OEMs. With the increase price of everything the aftermarket is helping smaller companies save on their repair costs in a highly competitive market.”

Challenges

What challenges do engine builders face today regarding sleeve technology today and related engine components?

“We know the Big Three car manufacturers bring in nearly all their cylinder liners from China and India,” says Metchkoff. “Domestic aluminum block motors with liners are simply not as good as they were twenty to fifty years ago. Therefore, if a domestic motor comes in for a rebuild, an aftermarket sleeve will immediately increase the reliability of that block.”

And don’t overlook performance opportunities, Metchkoff says. “Even more prolific are the Sport Compact or import cars being hot rodded. While these blocks are great for daily driving or cruising down the coast, when boost, turbo, etc., is brought into the motor for performance, the stock blocks distort or crack. Any engine builder with a good reputation will always recommend sleeving a block first, then proceed from that point,” he says.

Clinton says “All engine components are a marriage of design to accomplish the intended use. The cylinder, which is where the power is generated, needs to be able to accommodate what the engine designer planned, such as high compression, high rpm, high heat and so on.

“High rpm engines are able to produce horsepower equal to high torque engines because in a unit of time, there is more power pulses and as an aggregate they will equal a slower turning engine churning out high torque,” Clinton continues. “In the cylinder, the challenge is to manage the heat, provide the proper lubrication to seal the combustion process and have enough surface hardness to obviate wear. Part of this is accomplished with valve overlap to promote exhaust scavenging.”

Zimmerman says his company pays careful attention to those “slower turning engines” and their components.

“We focus on the diesel market which is lower revving engines (260-3000 RPM) rather than gas applications,” he says. “The receiver bore must be within specifications to avoid liner movement and flange breakage. Dry liners/sleeves must be fitted to allow for appropriate heat dissipation. The cylinder head will apply tremendous force to the liner when torqued; head bolt torque, liner protrusion and cylinder head flatness must be within specifications to avoid side loading the liner flange which could result in a cracked liner flange. Piston rings installed upside down will give the impression of a ‘bad’ liner when actually the engine was built incorrectly.”

What’s On The Horizon?

Zimmerman says some newer technology involves liner-less engines with sprayed on molten steel to create the liner wall. “While this technology is years away from the aftermarket it raises questions of what is the service life and how will the cylinder walls be repaired when a failure happens?” he asks. “Will these engines be as easy and cost effective to repair as today¹s engines?”

Choices, choices… Custom sleeves are available, each designed to fit your application’s individual cylinder bore as needed. Photo courtesy of PowerBore Cylinder Sleeves.

Asking “What’s next?” to Darton’s Clinton raises even more questions. “That’s the sixty-four dollar question,” he says. “We have competing interests in new engine production including electric, which really is the wave of the future, and lightweight, small cubic inch fossil fuel engines and hybrids. Excepting industrial engines, diesels, tractors and high performance engines, the long range future looks like a diminishing potential for engine builders to focus on this rebuilding process. Sleeving will always be with us in some form but it will take the engine building community to quickly analyze market changes and be flexible in staying ahead of changes.”

Staying with those changes may involve better replacements for familiar OE technology that has been developed to meet changing CAFE standards. “The 4.2L 6 cylinder Vortec GM OE sleeve had a flange on it,” said McDonell. “To reduce weight they made it very thin. These tended to crack between the flange and the barrel of the sleeve. We came out with an application that’s beefier than what the OE provided.”

In other cases, it’s looking at less familiar challenges. “Tesla would be our biggest concern,” says Metchkoff. “Electric car travel will change the engine building industry dramatically.”

However, our experts agree that sleeving will remain a viable business for the foreseeable future. “There will never be an end to sleeving engine blocks: there are simply too many of them worldwide,” concludes Metchkoff. “Frankly, the oil companies are probably our industry’s greatest ally. As long as gas or diesel powers our vehicles, there will always be opportunity for sleeving.”

Read More

- Types of cylinder liner

- Cylinder liner

- Installing Cylinder Liners

- Liner Failure Analysis and key points for how to work and repair the liner failure

- Products (types of diesel and petrol cylinder liner)

- What Is Cylinder Liner? | Material for Cylinder Liner | Function of Cylinder Liner | Types of Cylinder Liner

- What is a cylinder liner and the introduction of all types of cylinder liners in Gasoline and Diesel engines

- What is a cylinder liner?